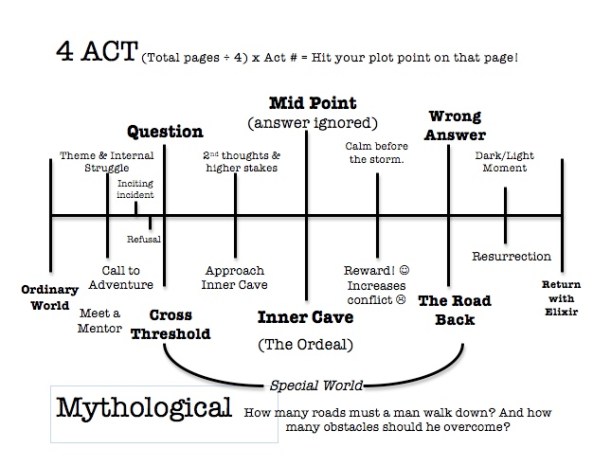

Every story needs an antagonist, and every writer needs to learn how to write them well. This is no easy task, as the point of the hero’s journey is usually to uphold your view of the world, and the antagonist – it should go without out saying – threatens that world view. Back in the day, you could just write good guy/bad guy scenarios where the lines between good and evil were clearly defined, and good always prevailed, but let’s face it: people are bored with that! No, no. What today’s audiences want, and frankly, what we as writers want too, is for movies to be living testaments to the human experience. Let’s take a lesson from the Impressionist painters and realize that black and white do not exist in nature: only shades of grey. Let us think then, if this is our pallet, what can we paint with it?

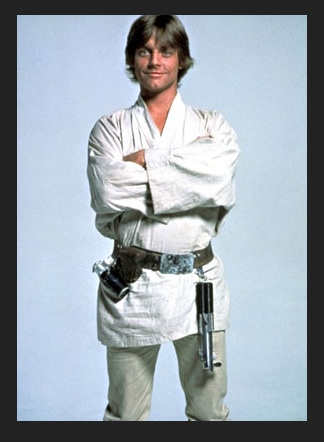

If our audiences are bored with good prevails over evil, then let’s begin with these two concepts. Good. Not that tricky. That’s what makes this dreary, drab, dull place called Earth seem tolerable. Evil. Also not that tricky. It is that which makes this glorious, euphoric, orgasmic place called Earth seem dreary, drab, and dull in the first place. Now how to take those things and turn them into unique and engaging characters?

It’s actually not that difficult. All you have to do in order to get into the mind of your antagonist is remember that there is no such thing as evil; rather that there is a dangerous propensity within the human mind for rationalizing even the most inhumane and illogical thoughts. Be it from he- said-she-said, to Nazi’s killing Jews, life is simply absurd.

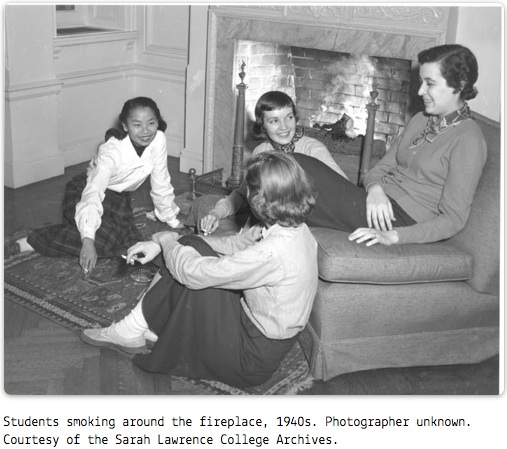

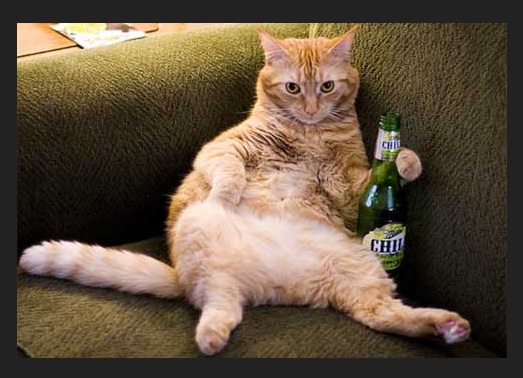

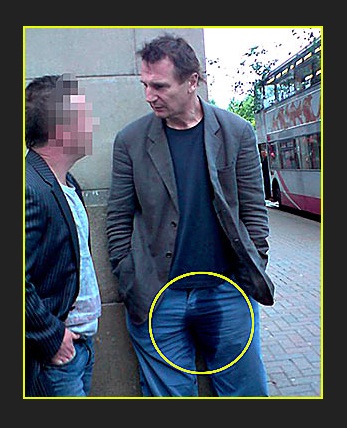

Just like this is absurd. Funny only because that cat is harmless. I will point out to that the cat’s stash is just part of his nature. While environment and circumstances to play a huge role in shaping real people & fictional characters, NEVER FORGET that “born this way” is a real thing. The nervous system, taste buds, other senses, brain chemistry, genetic coding, pheromones…all that plays a huge part in making a person who they are.

So yeah, life is absurd, but there is some order amid all the chaos. Realize it. Recognize it. Write about it. The more sense you try to make out of your characters, the better, especially when it comes to your antagonists. In some respects, they should be more fleshed out that your antagonists since they come into the story on the losing side. “The losing side of what?” you might ask. Popular opinion, that’s what. That includes your audience’s opinion and your own. The problem then boils down to an issue of respect, and before you set pen to paper in the effort to describe them you must ask yourself, “Do I respect this character?” And to that effect, “Are they a force to be reckoned with?” The two are mutually exclusive: for your antagonist to be a worthy opponent, he or she must be powerful, and the concept of power – as we all know – is relative to our own weaknesses. As the documentors of these living testaments to the human experience that we call films, we need to ask ourselves these questions.

There will be times in your life of writing when the character that’s screaming their story in your ear is the type of person whose ideological beliefs differ from yours, and whose moral compass points in a direction you’ve never even heard of, or that you have, at least, tried to steer clear of. Take heart, for the question you should be asking yourself is not, “Should I write this character?” but rather, “How should I tell their story?” Villainous, devious, malcontent; these have been the cornerstones of some of cinema’s greatest protagonists since D.W. Griffith (not so much a nice guy himself) paved the way for gangster films with “The Musketeers of Pig Alley.” And it’s only natural. There is no light without the darkness after all, right?